Uighur Identity in Xinjiang

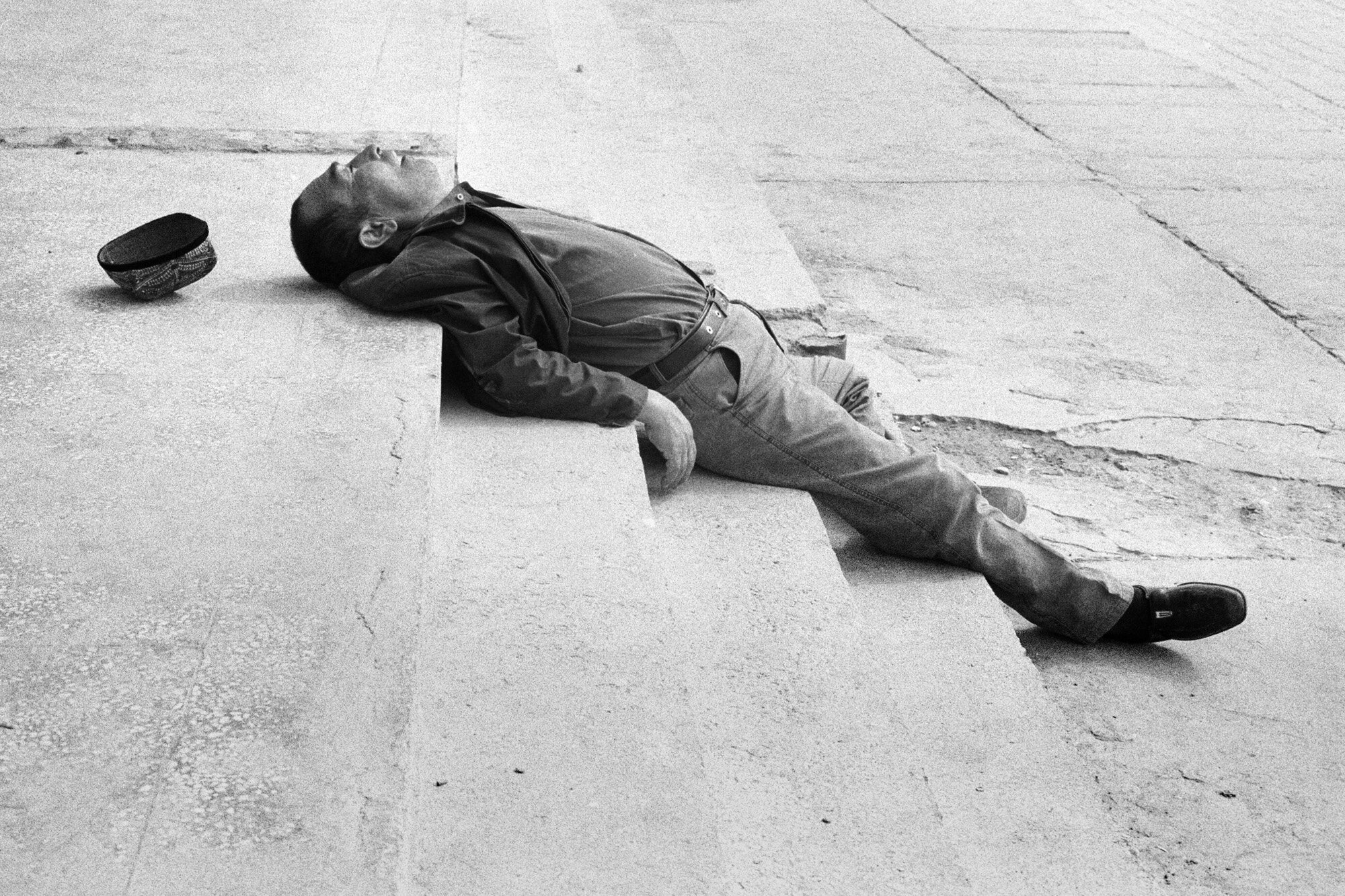

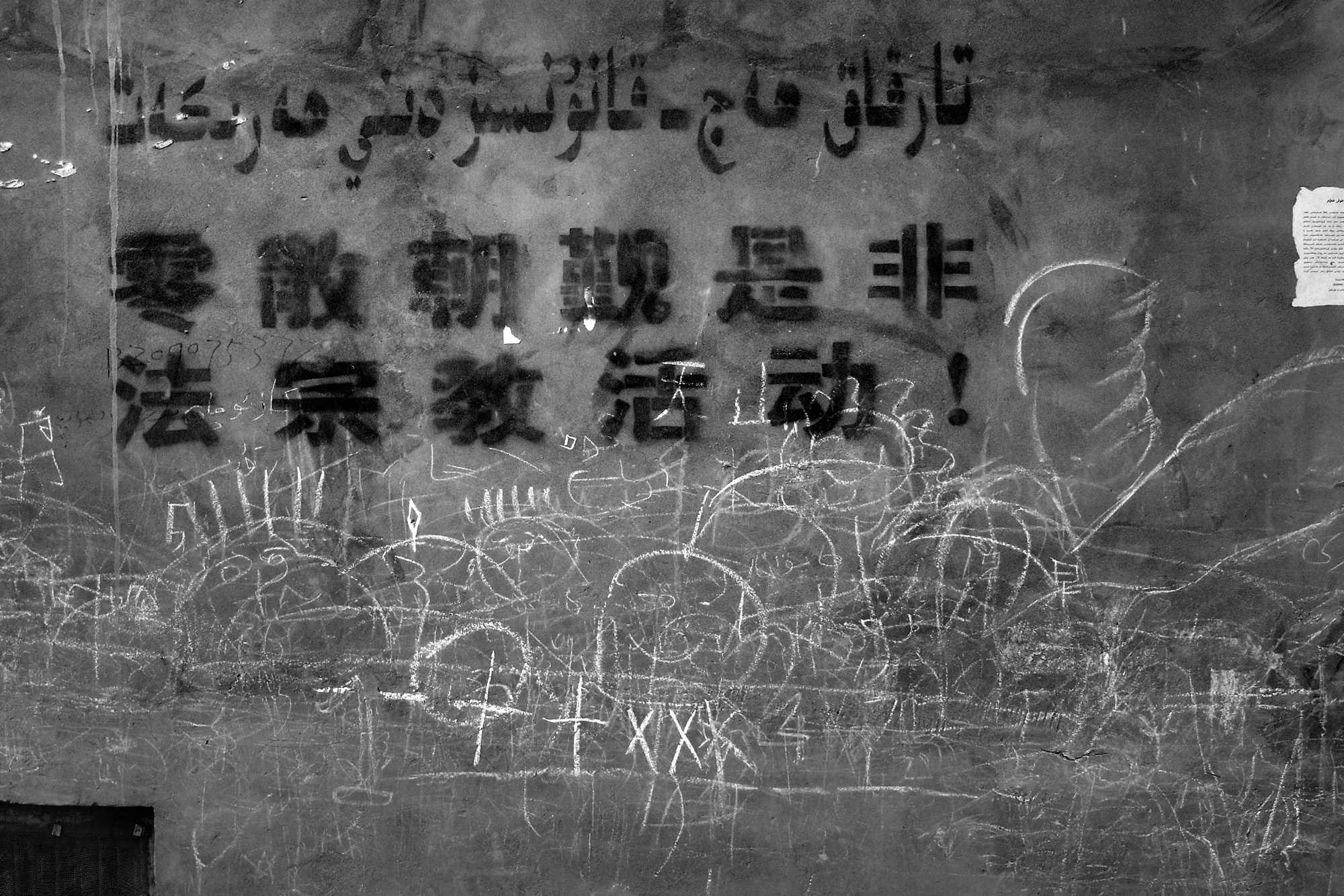

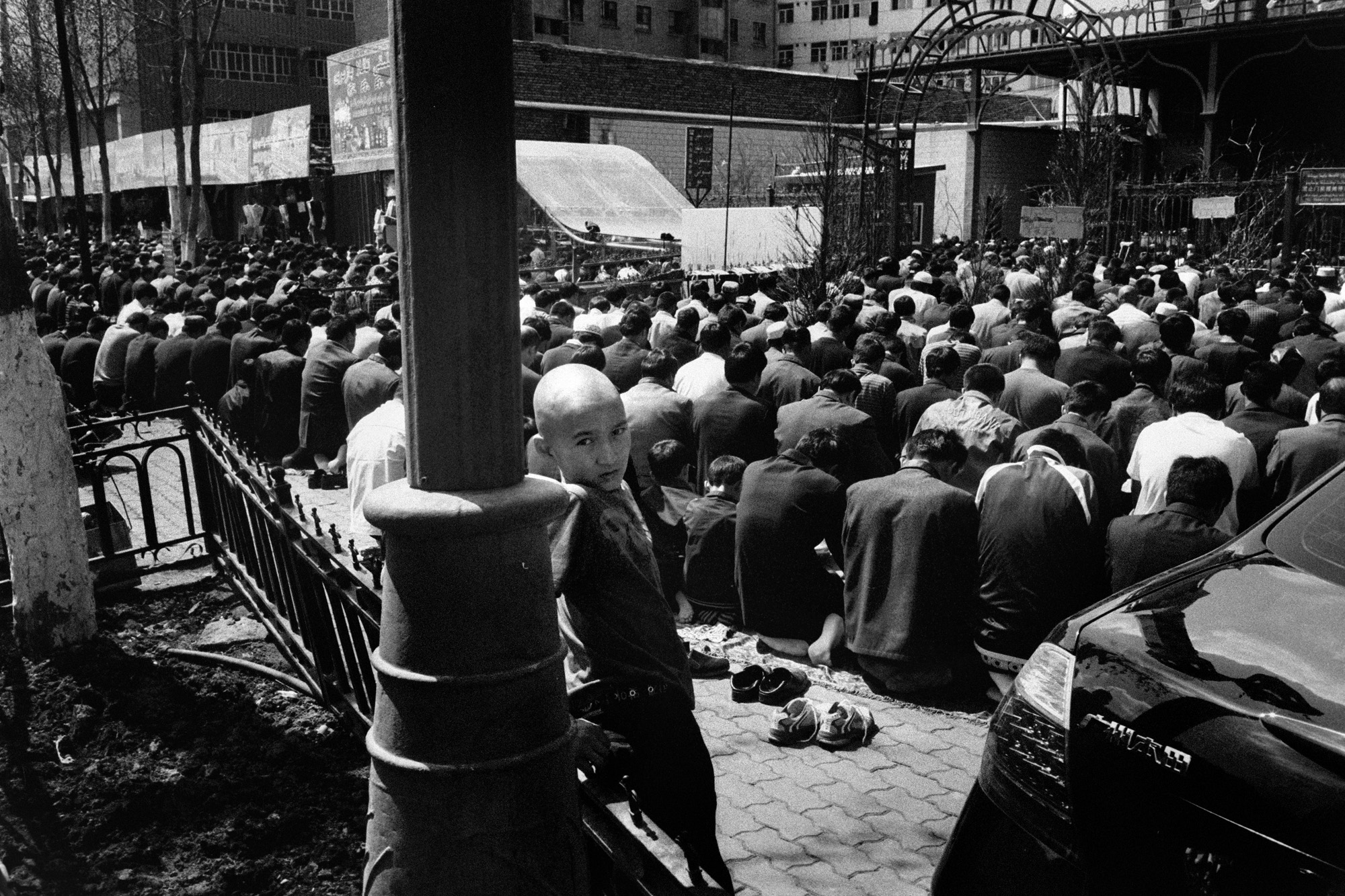

In recent years, China’s efforts to control the Uighur residents of Xinjiang has emerged as a contentious subject of human rights criticism, with reports of mass detention in “re-education” camps.

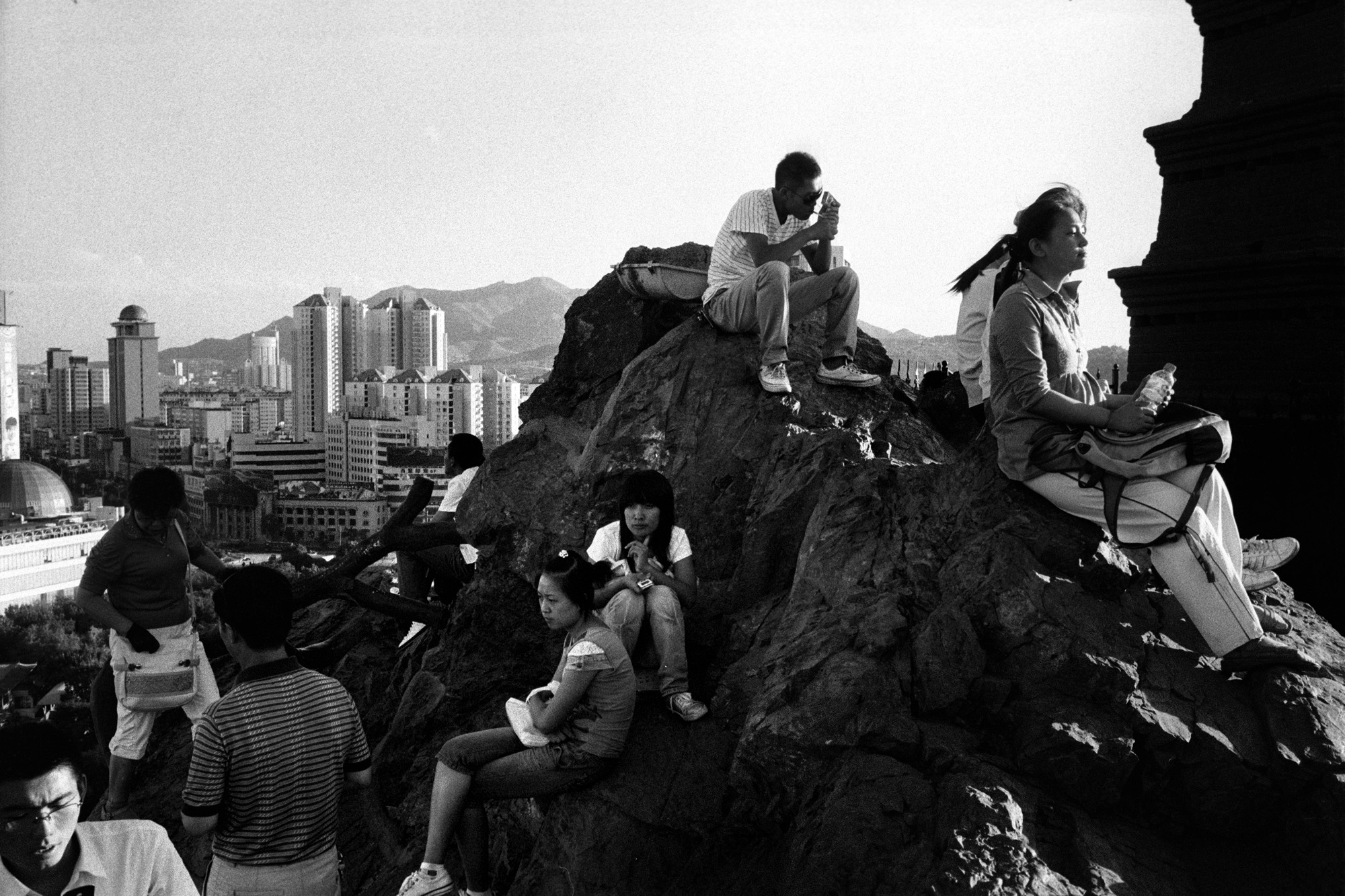

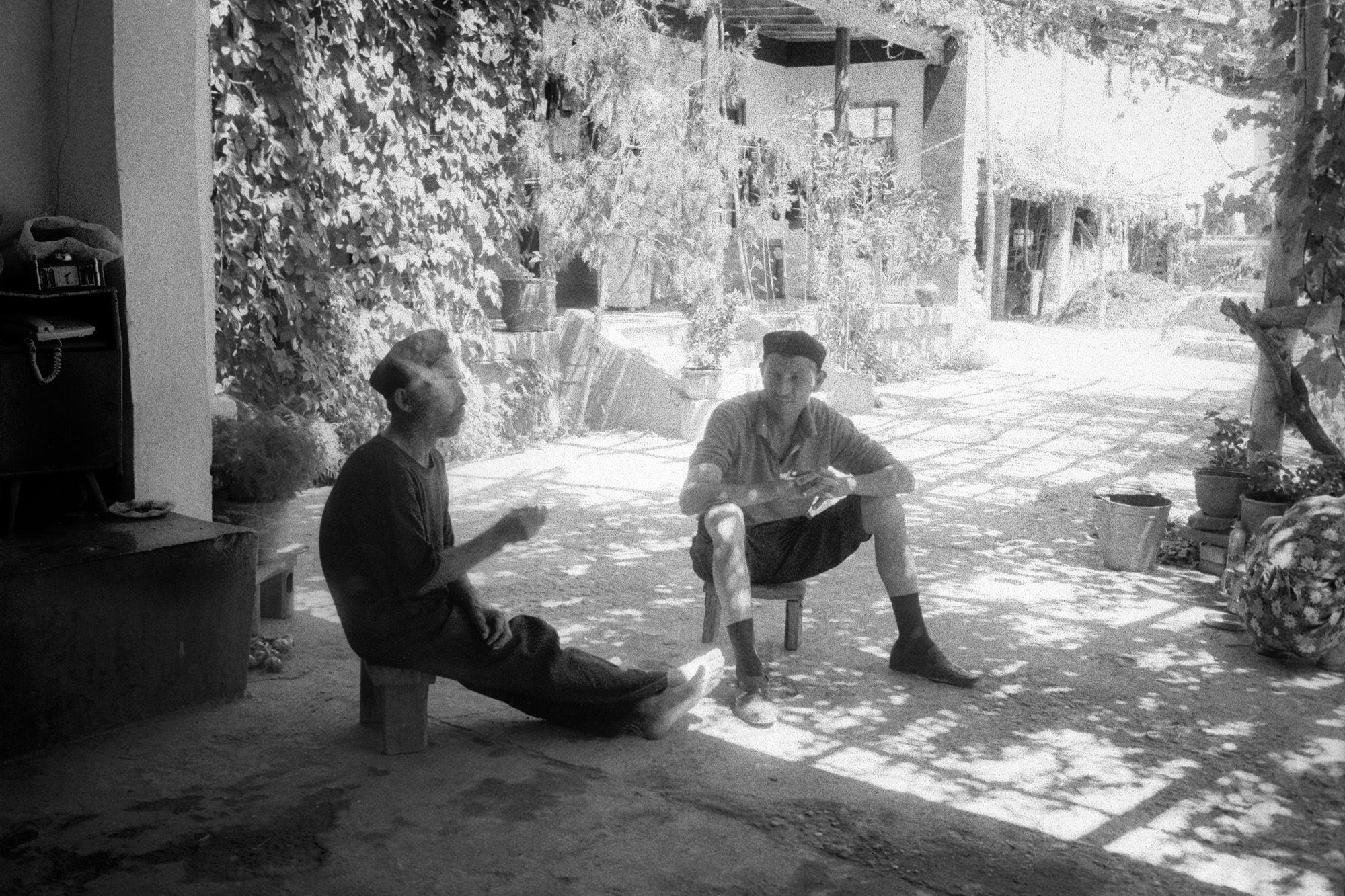

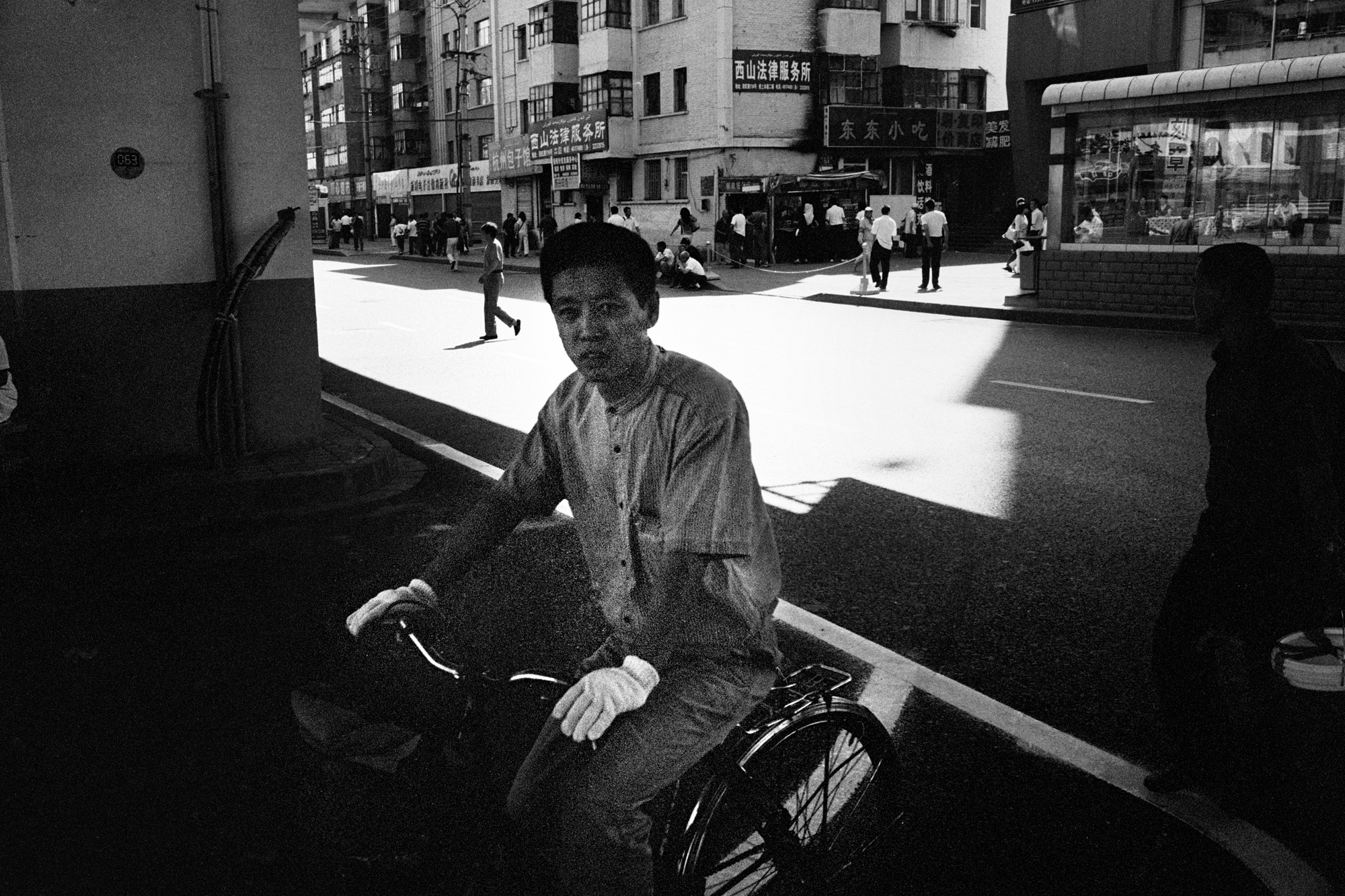

I first visited Xinjiang in 2008, when Chinese policies in the region were only beginning to harden. At the time, China was eagerly anticipating its Olympic hosting debut, and I wanted to witness this international ascendency from Xinjiang, a place where China’s projection of national harmony has long met a more complicated reality.

I stayed for 4 months, traveling throughout the region and slowly picking up the language. Ultimately, while looking into reports that a police station was torched in the small town of San Gong, I was detained by police and eventually deported into neighboring Kazakhstan. I had missed the start of the Olympics by a few weeks.

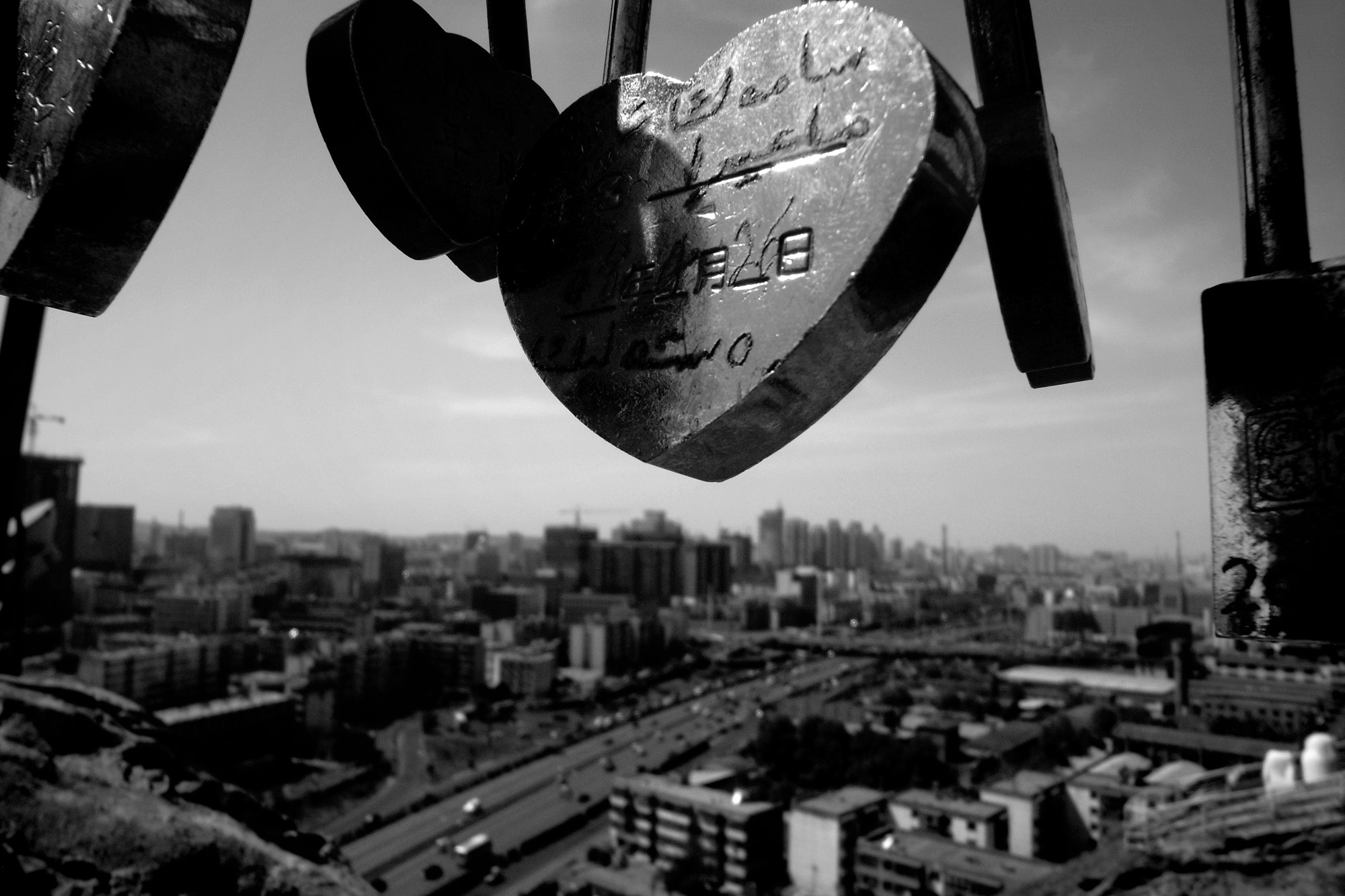

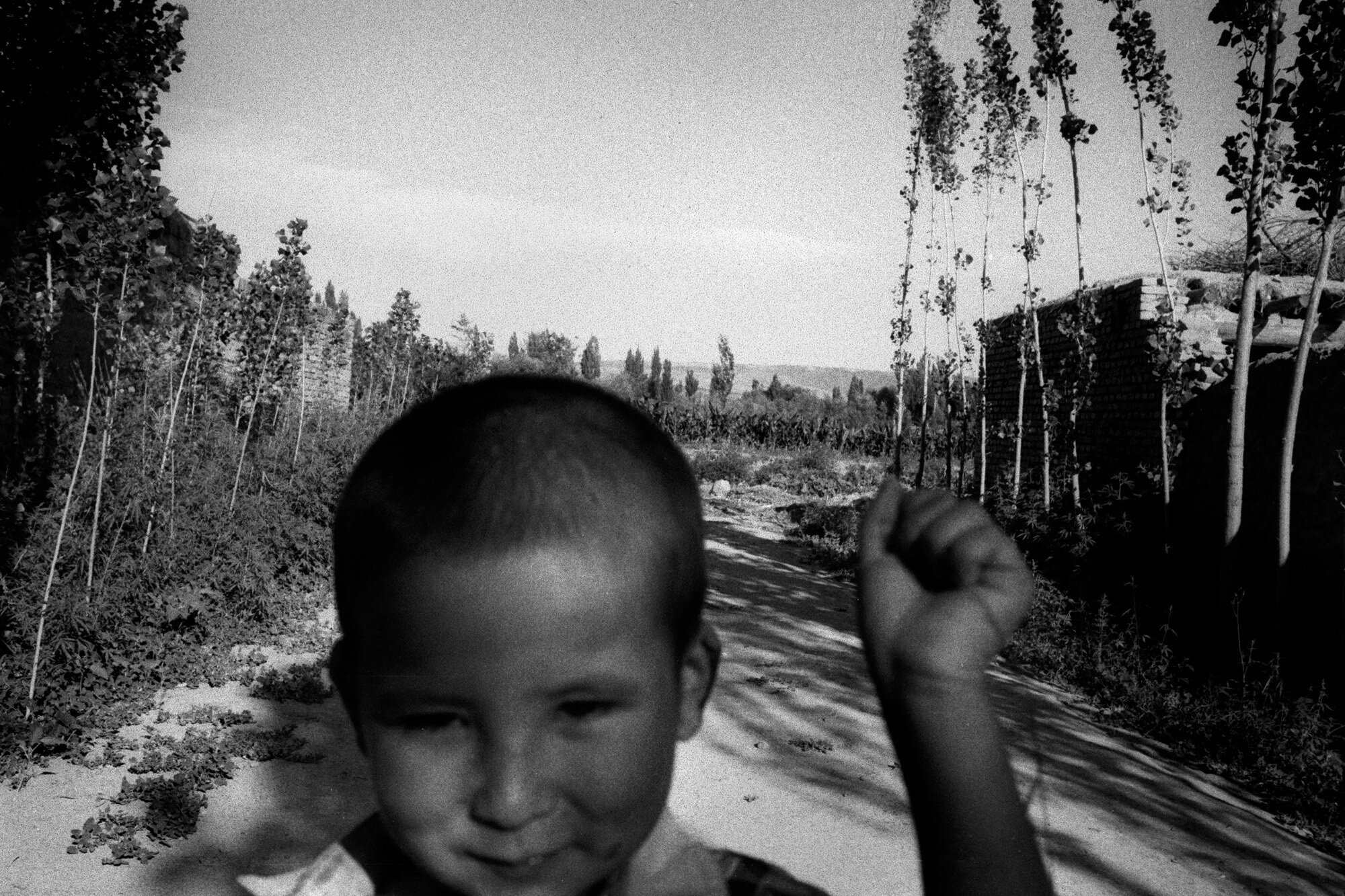

The Uighurs of Xinjiang are ethnic minorities who share closer historic and cultural ties to the Muslim Turkic groups of Central Asia. Racism, language barriers, and lack of access to higher education prevent many young Uighurs from getting jobs in the new Chinese economy, all while their traditional roles as traders and farmers became unprofitable.

As Han Chinese influences became increasingly prevalent in their hometowns, many young Uighurs I spoke to looked for ways to adapt, nursing plans to learn English and start an exporting business in Shanghai or learn Arabic and study the Quran at Al-Azhar in Cairo. Travel restrictions would stand in the way of either dream.

Left: A statue in Hotan’s main square shows Mao Zedong shaking hands with an old Uighur man. As the government’s story goes, Kurban Tulum was a Uighur laborer born in 1883 in the Keriya oasis. When the People’s Liberation Army marched into Xinjiang after the 1949 revolution, Kurban Tulum rode his donkey more than 1,000km around the Taklamakan Desert to bring grapes and a melon as a symbol of appreciation. Party officials saw the opportunity to present him as a symbol of Uighur-Han cooperation, and flew him to Beijing to meet with Mao Zedong, their handshake memorialized first in a photo and later in this monument.

Center: The Olympic torch was greeted by large crowds as it traveled around China, but in Xinjiang residents were told to stay inside while the streets were lined with police and a highly selected group of workers and school children. In this picture, police and military watch an Urumqi alleyway that runs parallel to the torch route.

Right: Immediately after the Olympic torch passed through Urumqi, groups of workers line up for a commemorative photo.